This piece from the Japanese paper Asahi on migration in Asia caught my eye:

Asia: S. Korea, Singapore turn birthrate tide with immigration

BY TAKESHI KAMIYA, THE ASAHI SHIMBUN

SEOUL--Declining birthrates are a problem that Japan shares with South Korea and Singapore.

But unlike Japan, which has yet to open its doors widely to immigration, these two countries are welcoming people from elsewhere in Asia to fill the gap.

In South Korea, the main struggle has been felt in depopulated farm and fishing villages.

Now, brides from China and Southeast Asian countries are settling down with local bachelors hoping to raise the next crop of farmers.

In Singapore, the government plans to bring in about 2 million immigrants--or nearly half of the current population--to maintain growth.

The squalling of babies is a welcome sound these days among the roughly 40 households in Guzi village in Jeollabuk-do province in southwestern South Korea.

Rice farmer Paek In Ki, 37, and his Vietnamese wife, Tran Thi Thanh Thuy, 25, welcomed their first child--a girl--in 2004. Their son was born late last year. The couple wed in 2003.

In this traditional farming village, Confucianism still exerts a strong influence. Thanh Thuy cooks up local delicacies to celebrate Confucian events, and she works in the rice paddies and strawberry fields alongside her husband.

"She is now a crucial member of this village," Paek said.

Thanh Thuy says she feels right at home. "The farming and Confucian events are similar to the way I grew up in Vietnam. I don't feel any difference here," she said.

International marriages are on the rise in rural South Korea. According to the Korea National Statistical Office, of about 8,600 farmers, forestry workers and fishermen who got married in 2006, 41 percent got hitched to women from other countries.

Of all South Korean men who married foreign women in 2006, about 11,000 took Vietnamese brides, a 74 percent rise from the previous year. Many marriages were made through brokers.

Not all those matches were love at first sight, but appearance did play a factor.

Paek cited a pragmatic reason for choosing Thanh Thuy. "She looks South Korean, so I thought our children would not face discrimination," he said.

In 2005, the South Korean birthrate--the number of children a woman has in her lifetime--fell to 1.08 children on average. That figure was even lower than Japan's birthrate of 1.26 and ranks among the world's lowest.

Moreover, in rural villages, the gender imbalance is growing wider, in part because of fetal sex selection techniques, similar to those that have led to serious population problems in China and India.

According to Yang Soon Mi, an official of the National Rural Development Institute, illegal prenatal sex selection is rising because of the declining birthrate and a traditional preference for male children.

Some estimates show that, within three years, the male-to-female imbalance will widen to 120 to 100.

The shortage of brides in rural areas has led male villagers to head to cities. That has reduced the work force, and in turn, led to fewer young families and fewer children in the countryside.

However, it is often difficult for women from other cultures to fit in with Korean farm families, leading some to give up and return home in defeat.

The biggest troubles are communicating with their husbands or their mothers-in-law.

According to a support group for foreign women, one woman was rejected by her husband when he discovered that she was sterile. Another woman said that her husband physically abused her when she disobeyed her mother-in-law's dictates.

South Korea's Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry now regards immigrant women as important "human resources for farm villages." It is working to make things easier on these Asian brides.

This year, the ministry is training 300 counselors who will teach immigrant women the Korean language or offer advice on common problems. The counselors are being dispatched throughout South Korea's farming villages.

The government is also offering financial assistance to enable the foreign brides to afford trips to their home countries to see the families they left behind.

Most of these marriages were arranged through brokers, which has led some international human rights organizations in the United States and Europe to label them "marriages close to human trafficking."

However, according to Yang, "Foreign women are now indispensable to South Korea's farming villages. They can really improve things, so we should not view them negatively. We need to create ways to help them soon."

In Singapore, meanwhile, a ceremony was held in mid-April at a public hall in the eastern part of the city-state to welcome 91 people who had just been granted Singaporean citizenship. The immigrants were mostly from India, China and Malaysia.

After receiving a citizenship certificate from Deputy Prime Minister Shunmugam Jayakumar, each newcomer placed his or her right hand on their heart and swore, "We, Singaporean citizens, pledge to build a democratic society irrespective of race, language or religion."

Jayakumar congratulated the group, and said that both Singapore's native citizens and its adopted brethren must make efforts to get along.

In March, the Singaporean government said it plans to raise the population from the current 4.5 million to 6.5 million through immigration.

Singapore's birthrate fell to 1.25 per woman in 2006.

Pauline Straughan, an associate professor of medical sociology at the National University of Singapore, cited these reasons for the decline:

・Married couples with higher education have increased, and they spend much money for the education of their children. Thus, they are having fewer children.

・Temporary employment contracts of one to two years are on the rise, leaving would-be mothers unable to afford to become pregnant. That is because maternity leaves could obstruct their promotion.

Straughan noted that, as long as young people have uncertain job prospects, the birthrate will never rebound.

Singapore's increased immigration policy is a desperate measure to retain its prosperity and battle the declining birthrate.

However, hurdles for obtaining permanent residency or citizenship are high, as the main reason for accepting immigrants is economic growth. Preference is given to immigrants who bring with them skills and wealth to contribute to Singapore's future.

Unskilled workers, meanwhile, are unwelcome, in part because of fears of social unrest.

In 2003, the government began granting permanent residence status to individuals who had invested at least S$2 million (about 160 million yen) in the country per person through real estate or stock purchases, among other investments.

Researchers in fields such as information technology or biotechnology are also welcome to apply for permanent residency. This year, the government began issuing working visas that make it easier for highly skilled workers to find employment in Singapore.

But Singapore also imposed strict restrictions on its about 500,000 unskilled immigrant workers, which include maids and construction workers. Such workers can only live in certain areas and are prohibited from marrying people with Singaporean citizenship or permanent residency.

Female temporary workers face deportation if they become pregnant.

In addition, many Singaporean citizens fear competition for jobs could intensify with a rise in immigrants.

"We have to work harder not to lose our jobs. We are too busy working to raise our own children, which is why the birthrate is falling," said a 38-year-old Singaporean man who runs a consulting firm. His wife, 34, is a national library employee.

Each year, 10,000 to 13,000 people become citizens, and about 50,000 people receive permanent residency.

However, Singapore's Ministry of Home Affairs does not reveal details on their origins, fearing a backlash could worsen diplomatic relations with their home countries, officials said.

Friday, June 29, 2007

Thursday, June 28, 2007

Tuesday, June 26, 2007

Migration's Flip Side

From the IHT:

In this poor but proud farming region, where many of the small wooden houses have no electricity and people still read by candlelight, nearly every third home sits empty. Their occupants have gone to pick mushrooms in Ireland.

When Laima Muktupavela left more than three years ago, she moved into a dusty three-room house near Dublin with 11 other Latvians and picked mushrooms from 6 a.m. to sundown. The farm's owner forbade the Latvians to wear gloves and the mushrooms quickly turned her fingers black. She sautéed mushrooms for breakfast, lunch and dinner. She earned about 215, or $250, a week - more than one and a half times the monthly minimum wage back home - and splurged on a new gray wool coat.

Back in Latvia, her four children felt abandoned. Her 16-year-old daughter, Anna, sent angry letters in envelopes filled with her baby pictures. Her partner, who is now her husband, met someone else.

Tormented by the prospect of permanent exile, Muktupavela returned to Latvia. She wrote a book about her experiences, "The Mushroom Covenant," which tapped into the national fear about the growing exodus of Latvians to Ireland. It became a best seller.

"There is hardly a family left in this country who hasn't lost a son or daughter or mother or father to the mushroom farms of Ireland," said Muktupavela, an ebullient 43-year-old.

She pointed to a vast field peppered with abandoned houses, their occupants departed to the handful of European Union countries - Ireland, Sweden, Britain - that opened their borders to the bloc's newest members when they joined in May 2004.

Freedom to cross the EU's borders unhindered was a reward of membership that natives in this Baltic country of 2.3 million people aspired to after 50 years of Soviet occupation.

But as other EU countries grapple with whether to admit inexpensive laborers from Eastern and Central Europe, fearful that it will undermine their social standards, the case of Latvia shows how migration can exact a heavy toll on the country they leave behind.

While there are no official statistics, Latvian officials estimate that 50,000 to 100,000 people have emigrated over the last 18 months, as many as 25,000 of them to Ireland. In the latest high-profile departure, Latvians watched with horror last month when the Olympic biathlete Jekabs Nakums announced on television that he was leaving to go wash cars in Ireland.

The exodus of economic migrants from Eastern Europe to their wealthier neighbors in the West has been a growing phenomenon since EU expansion last year. But the trend has been particularly pronounced in Latvia because the country's average monthly minimum wage of 90 lats, or 130, is the lowest in the 25-member bloc, while price increases since accession have been highest here.

In this poor but proud farming region, where many of the small wooden houses have no electricity and people still read by candlelight, nearly every third home sits empty. Their occupants have gone to pick mushrooms in Ireland.

When Laima Muktupavela left more than three years ago, she moved into a dusty three-room house near Dublin with 11 other Latvians and picked mushrooms from 6 a.m. to sundown. The farm's owner forbade the Latvians to wear gloves and the mushrooms quickly turned her fingers black. She sautéed mushrooms for breakfast, lunch and dinner. She earned about 215, or $250, a week - more than one and a half times the monthly minimum wage back home - and splurged on a new gray wool coat.

Back in Latvia, her four children felt abandoned. Her 16-year-old daughter, Anna, sent angry letters in envelopes filled with her baby pictures. Her partner, who is now her husband, met someone else.

Tormented by the prospect of permanent exile, Muktupavela returned to Latvia. She wrote a book about her experiences, "The Mushroom Covenant," which tapped into the national fear about the growing exodus of Latvians to Ireland. It became a best seller.

"There is hardly a family left in this country who hasn't lost a son or daughter or mother or father to the mushroom farms of Ireland," said Muktupavela, an ebullient 43-year-old.

She pointed to a vast field peppered with abandoned houses, their occupants departed to the handful of European Union countries - Ireland, Sweden, Britain - that opened their borders to the bloc's newest members when they joined in May 2004.

Freedom to cross the EU's borders unhindered was a reward of membership that natives in this Baltic country of 2.3 million people aspired to after 50 years of Soviet occupation.

But as other EU countries grapple with whether to admit inexpensive laborers from Eastern and Central Europe, fearful that it will undermine their social standards, the case of Latvia shows how migration can exact a heavy toll on the country they leave behind.

While there are no official statistics, Latvian officials estimate that 50,000 to 100,000 people have emigrated over the last 18 months, as many as 25,000 of them to Ireland. In the latest high-profile departure, Latvians watched with horror last month when the Olympic biathlete Jekabs Nakums announced on television that he was leaving to go wash cars in Ireland.

The exodus of economic migrants from Eastern Europe to their wealthier neighbors in the West has been a growing phenomenon since EU expansion last year. But the trend has been particularly pronounced in Latvia because the country's average monthly minimum wage of 90 lats, or 130, is the lowest in the 25-member bloc, while price increases since accession have been highest here.

Sunday, June 24, 2007

Latvia and Kaliningrad

This, from the Itar-Tass News Agency:

Latvia encourages ethnic Russians to move to Kaliningrad

21.06.2007, 16.05

KALININGRAD, June 21 (Itar-Tass) - Latvian companies are prepared to build housing in the Kaliningrad region for people resettled from Latvia, a meeting of Vice- premier of the Kaliningrad government Yuri Shalimov with President of the Russo-Latvian Association for Cooperation Boris Katkov and representatives of Latvian construction companies was told, the press service of the Kaliningrad government told Tass.

Many people in Latvia would like to move to the Kaliningrad region, Katkov said. Young educated people who want to open their own business account for the biggest share of potential residents. As many as 109 families have been preparing documents in the framework of a state Program of Resettlement of Compatriots, and around 500 are on waiting list. The number of those who wish to move to the Kaliningrad region might grow given a better opportunity of housing in the Kaliningrad region, Katkov said.

Latvian businessmen suggested that every family moving to Russia might lease their houses in Latvia and used the money raised to pay off credits borrowed at Latvian banks for purchase of housing. Latvian construction companies want to build several compounds in the Kaliningrad region, employing construction workers from Kaliningrad construction companies.

A first group of people resettled from Latvia arrived in the Kaliningrad region last week. The Kaliningrad region is planning to accommodate around 300,000 compatriots in the following five years.

Latvia encourages ethnic Russians to move to Kaliningrad

21.06.2007, 16.05

KALININGRAD, June 21 (Itar-Tass) - Latvian companies are prepared to build housing in the Kaliningrad region for people resettled from Latvia, a meeting of Vice- premier of the Kaliningrad government Yuri Shalimov with President of the Russo-Latvian Association for Cooperation Boris Katkov and representatives of Latvian construction companies was told, the press service of the Kaliningrad government told Tass.

Many people in Latvia would like to move to the Kaliningrad region, Katkov said. Young educated people who want to open their own business account for the biggest share of potential residents. As many as 109 families have been preparing documents in the framework of a state Program of Resettlement of Compatriots, and around 500 are on waiting list. The number of those who wish to move to the Kaliningrad region might grow given a better opportunity of housing in the Kaliningrad region, Katkov said.

Latvian businessmen suggested that every family moving to Russia might lease their houses in Latvia and used the money raised to pay off credits borrowed at Latvian banks for purchase of housing. Latvian construction companies want to build several compounds in the Kaliningrad region, employing construction workers from Kaliningrad construction companies.

A first group of people resettled from Latvia arrived in the Kaliningrad region last week. The Kaliningrad region is planning to accommodate around 300,000 compatriots in the following five years.

Nikkeijin in Japan

There is this recent study from the World Bank:

What do we know about the Japan-Brazil migration and remittance corridor?

Junichi Goto, Kobe University, Japan

Since the revision of the Japanese immigration law in 1990, there has been a dramatic influx of Latin Americans, mostly Brazilians, of Japanese origin (Nikkeijin) working in Japan. The immigration of more than 250,000 Nikkeijin in Japan is likely to have a significant impact on both the Brazilian and the Japanese economies, given the substantial amount of remittances they send to Brazil. The impact is likely to be felt especially in the Nikkeijin community in Brazil. In spite of their importance, the detailed characteristics of Nikkei migrants and the prospect for future migration and remittances are under-researched. The purpose of WPS4203 is therefore to provide a more comprehensive account of the migration of Nikkeijin workers to Japan. The paper contains a brief review of the history of Japanese emigration to Latin America (mostly Brazil), a study of the characteristics of Nikkeijin workers in Japan and their current living conditions, and a discussion on trends and issues regarding immigration in Japan and migration policy. The final part of the paper briefly notes the limitation of existing studies and describes the Brazil Nikkei Household Survey, which is being conducted by the World Bank's Development Research Group at the time of writing this paper. The availability of the survey data will contribute to a better understanding of the Japan-Brazil migration and remittance corridor.

What do we know about the Japan-Brazil migration and remittance corridor?

Junichi Goto, Kobe University, Japan

Since the revision of the Japanese immigration law in 1990, there has been a dramatic influx of Latin Americans, mostly Brazilians, of Japanese origin (Nikkeijin) working in Japan. The immigration of more than 250,000 Nikkeijin in Japan is likely to have a significant impact on both the Brazilian and the Japanese economies, given the substantial amount of remittances they send to Brazil. The impact is likely to be felt especially in the Nikkeijin community in Brazil. In spite of their importance, the detailed characteristics of Nikkei migrants and the prospect for future migration and remittances are under-researched. The purpose of WPS4203 is therefore to provide a more comprehensive account of the migration of Nikkeijin workers to Japan. The paper contains a brief review of the history of Japanese emigration to Latin America (mostly Brazil), a study of the characteristics of Nikkeijin workers in Japan and their current living conditions, and a discussion on trends and issues regarding immigration in Japan and migration policy. The final part of the paper briefly notes the limitation of existing studies and describes the Brazil Nikkei Household Survey, which is being conducted by the World Bank's Development Research Group at the time of writing this paper. The availability of the survey data will contribute to a better understanding of the Japan-Brazil migration and remittance corridor.

Demographic Benefits of Migration

A recent working paper from the World Bank:

Summary: The view that international migration has no impact on the size of world population is a sensible one. But the author argues, migration from developing to more industrial countries during the past decades may have resulted in a smaller world population than the one which would have been attained had no international migration taken place for two reasons: most of recent migration has been from high to low birth-rate countries, and migrants typically adopt and send back to their home countries models and ideas that prevail in host countries. Thus, migrants are potential agents of the diffusion of demographic modernity, that is, the reduction of birth rates among nonmigrant communities left behind in origin countries. This hypothesis is tested with data from Morocco and Turkey where most emigrants are bound for the West, and Egypt where they are bound for the Gulf. The demographic differentials encountered through migration in these three countries offer contrasted situations-host countries are either more (the West) or less (the Gulf) advanced in their demographic transition than the home country. Assuming migration changes the course of demographic transition in origin countries, the author posits that it should work in two opposite directions-speeding it up in Morocco and Turkey and slowing it down in Egypt. Empirical evidence confirms this hypothesis. Time series of birth rates and migrant remittances (reflecting the intensity of the relationship kept by emigrants with their home country) are strongly correlated with each other. Correlation is negative for Morocco and Turkey, and positive for Egypt. This suggests that Moroccan and Turkish emigration to Europe has been accompanied by a fundamental change of attitudes regarding marriage and birth, while Egyptian migration to the Gulf has not brought home innovative attitudes in this domain, but rather material resources for the achievement of traditional family goals. Other data suggest that emigration has fostered education in Morocco and Turkey but not in Egypt. And as has been found in the literature, education is the single most important determinant of demographic transition among nonmigrant populations in migrants' regions of origin. Two broader conclusions are drawn. First, the acceleration of the demographic transition in Morocco and Turkey is correlated with migration to Europe, a region where low birth-rates is the dominant pattern. This suggests that international migration may have produced a global demographic benefit under the form of a relaxation of demographic pressures for the world as a whole. Second, if it turns out that emigrants are conveyors of new ideas in matters related with family and education, then the same may apply to a wider range of civil behavior.

Summary: The view that international migration has no impact on the size of world population is a sensible one. But the author argues, migration from developing to more industrial countries during the past decades may have resulted in a smaller world population than the one which would have been attained had no international migration taken place for two reasons: most of recent migration has been from high to low birth-rate countries, and migrants typically adopt and send back to their home countries models and ideas that prevail in host countries. Thus, migrants are potential agents of the diffusion of demographic modernity, that is, the reduction of birth rates among nonmigrant communities left behind in origin countries. This hypothesis is tested with data from Morocco and Turkey where most emigrants are bound for the West, and Egypt where they are bound for the Gulf. The demographic differentials encountered through migration in these three countries offer contrasted situations-host countries are either more (the West) or less (the Gulf) advanced in their demographic transition than the home country. Assuming migration changes the course of demographic transition in origin countries, the author posits that it should work in two opposite directions-speeding it up in Morocco and Turkey and slowing it down in Egypt. Empirical evidence confirms this hypothesis. Time series of birth rates and migrant remittances (reflecting the intensity of the relationship kept by emigrants with their home country) are strongly correlated with each other. Correlation is negative for Morocco and Turkey, and positive for Egypt. This suggests that Moroccan and Turkish emigration to Europe has been accompanied by a fundamental change of attitudes regarding marriage and birth, while Egyptian migration to the Gulf has not brought home innovative attitudes in this domain, but rather material resources for the achievement of traditional family goals. Other data suggest that emigration has fostered education in Morocco and Turkey but not in Egypt. And as has been found in the literature, education is the single most important determinant of demographic transition among nonmigrant populations in migrants' regions of origin. Two broader conclusions are drawn. First, the acceleration of the demographic transition in Morocco and Turkey is correlated with migration to Europe, a region where low birth-rates is the dominant pattern. This suggests that international migration may have produced a global demographic benefit under the form of a relaxation of demographic pressures for the world as a whole. Second, if it turns out that emigrants are conveyors of new ideas in matters related with family and education, then the same may apply to a wider range of civil behavior.

Thursday, June 21, 2007

Tuesday, June 19, 2007

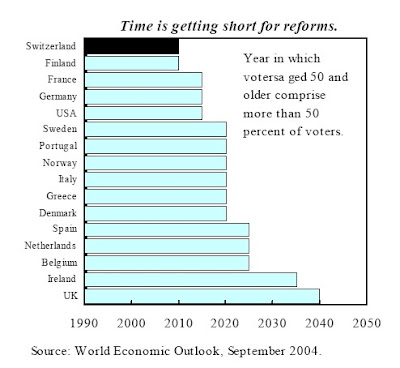

Over 50s: The Inbuilt Majority

Monday, June 18, 2007

German Births 2006

On June 5 the Federal Statistical Office published the following:

As previously reported by the Federal Statistical Office, provisional results for 2006 show decreasing numbers of births and deaths in Germany. The population, too, decreased slightly in that period.

In 2006, 673,000 live births were registered, that was 13,000 or 1.9% less than in 2005. The number of births has been declining since 1991, with the exception of 1996 and 1997. The number of deaths had fallen continuously from 1994 to 2001, before it increased in 2002, 2003 and 2005. In 2006, there were 822,000 deaths, which was a decrease by 8,000 or 1% on the previous year. This means that in 2006, there was an excess of deaths over births of about 149,000. In the previous year, the deficit of births was by about 5,000 persons smaller. On 31 December 2006, Germany had about 82,315,000 inhabitants. That was 123,000 or 0.1% less than at the end of 2005 (82,438,000).

Perhaps the most striking feature here is the decline in the absolute number of live births, this is known as the population momentum effect which operates as generations become smaller. Such is this effect now in Germany that the sheer wait of the numbers decline is likely to completely overwhelm any small increase we may see in the level of the TFR as birth recovery takes place among older women.

and remember, migration is roughly 0% now in Germany, with people leaving as fast as they are arriving.

As previously reported by the Federal Statistical Office, provisional results for 2006 show decreasing numbers of births and deaths in Germany. The population, too, decreased slightly in that period.

In 2006, 673,000 live births were registered, that was 13,000 or 1.9% less than in 2005. The number of births has been declining since 1991, with the exception of 1996 and 1997. The number of deaths had fallen continuously from 1994 to 2001, before it increased in 2002, 2003 and 2005. In 2006, there were 822,000 deaths, which was a decrease by 8,000 or 1% on the previous year. This means that in 2006, there was an excess of deaths over births of about 149,000. In the previous year, the deficit of births was by about 5,000 persons smaller. On 31 December 2006, Germany had about 82,315,000 inhabitants. That was 123,000 or 0.1% less than at the end of 2005 (82,438,000).

Perhaps the most striking feature here is the decline in the absolute number of live births, this is known as the population momentum effect which operates as generations become smaller. Such is this effect now in Germany that the sheer wait of the numbers decline is likely to completely overwhelm any small increase we may see in the level of the TFR as birth recovery takes place among older women.

and remember, migration is roughly 0% now in Germany, with people leaving as fast as they are arriving.

Sunday, June 17, 2007

Low Fertility in Europe

Just how extended the lowest-low fertility issue is in Europe at the present time(although please note the problem is by no means simply a European one, since several Asian countries - including possibly China - may well already be affected) can be seen from the following charts:

Number of European countries with the period TFR below 1.7, 1.5 and 1.3

(out of 39 countries with population above 100,000 in 2006)

(Please click over image for better viewing)

Proportion of Europeans living in countries with the period TFR below 1.7, 1.5 and 1.3 (2006)

(Please click over image for better viewing)

Number of European countries with the period TFR below 1.7, 1.5 and 1.3

(out of 39 countries with population above 100,000 in 2006)

(Please click over image for better viewing)

Proportion of Europeans living in countries with the period TFR below 1.7, 1.5 and 1.3 (2006)

(Please click over image for better viewing)

Migrants In Spain 2007

Below you can find the latest data from the Padron Municipal in Spain (provisional data, valid as from 1 January 2007). Amongst other points of interest the fact that migration from Morocco has now reduced to a trickle, that Romanians are arriving rapidly and now constitute the second largest group, that Ecuadorians seem to be moving on (maybe to Italy), and that some Argentinians may now be returning home, reflecting that countries relatively more rapid recent economic growth.

The first column represents the number of non Spanish nationals resident in Spain (by country) as of 1 January 2007, and the second column the % that each country represent of the total. Columns 3 and 4 show the same data for 1 January 2006, and columns 5 and 6 show the difference in absolute numbers and on a % basis.

(Please click over image for better viewing)

The first column represents the number of non Spanish nationals resident in Spain (by country) as of 1 January 2007, and the second column the % that each country represent of the total. Columns 3 and 4 show the same data for 1 January 2006, and columns 5 and 6 show the difference in absolute numbers and on a % basis.

(Please click over image for better viewing)

Women Who Don't Want Children

Another of the significant trends underlying low fertility in Europe is the increasing childlessness that can now be found in many parts of Europe. Motherhood is still nearly universal among the women in most Central and East European countries, where the proportion of women who reach age 50 childless is well below 10 percent and where relatively little change has been observed across cohorts.

In the rest of Europe, however, the proportion has now generally risen above 10 percent and is increasing. According to some estimates childlessness among women born after 1970 might approach 25 percent in countries like Austria, Germany (and specifically in the western parts), as well as in England and Wales. Unexpectedly for many observers, there has been increasing evidence that in some West European countries (specifically Austria, Germany, and the Netherlands), childlessness has emerged as an ideal life style among some groups. Data from the 2002 EuroBarometer survey indicate that over one in ten young women (aged 18 to 34) in these countries declared “none” as the ideal number of children (see chart below).

(Please click over image for better viewing)

Of course it needs to be borne in mind here that there is also considerable evidence accumulating that involuntary childlessness is on the rise. Some of this increase is driven by factors related to union formation (i.e. the inability to find a suitable partner); another part, by biological factors (infertility). The levels and trends in infertility are difficult to ascertain because of definitional and measurement issues, however, there is evidence that as postponement has pushed births towards the end of a woman’s reproductive years, where fecundability is reduced, sterility is higher, and the risk of miscarriage increases, and in general more and more women report problems becoming pregnant. In some countries of Eastern Europe and the Commonwealth of Independent States, two other factors are often quoted as contributing to increasing infertility - the high incidence of repeat abortion, and the spread of sexually transmitted infections (STIs).

In the rest of Europe, however, the proportion has now generally risen above 10 percent and is increasing. According to some estimates childlessness among women born after 1970 might approach 25 percent in countries like Austria, Germany (and specifically in the western parts), as well as in England and Wales. Unexpectedly for many observers, there has been increasing evidence that in some West European countries (specifically Austria, Germany, and the Netherlands), childlessness has emerged as an ideal life style among some groups. Data from the 2002 EuroBarometer survey indicate that over one in ten young women (aged 18 to 34) in these countries declared “none” as the ideal number of children (see chart below).

(Please click over image for better viewing)

Of course it needs to be borne in mind here that there is also considerable evidence accumulating that involuntary childlessness is on the rise. Some of this increase is driven by factors related to union formation (i.e. the inability to find a suitable partner); another part, by biological factors (infertility). The levels and trends in infertility are difficult to ascertain because of definitional and measurement issues, however, there is evidence that as postponement has pushed births towards the end of a woman’s reproductive years, where fecundability is reduced, sterility is higher, and the risk of miscarriage increases, and in general more and more women report problems becoming pregnant. In some countries of Eastern Europe and the Commonwealth of Independent States, two other factors are often quoted as contributing to increasing infertility - the high incidence of repeat abortion, and the spread of sexually transmitted infections (STIs).

Quantum or Tempo?

This is the fundamental question that the experts have been asking themselves when it comes to interpreting the decline in birth rates. This question arises because the levels and trends in period fertility indicators, like the Total Fertility Rate (TFR), could be driven by either one of two mechanisms: changes in the number of children that women have, and changes in the timing of births. The TFR measures the average number of births a woman would have by the time she reaches the end of her reproductive years, if she experiences the age-specific fertility rates observed in a given period. This measure “transposes” a momentary experience across the lifetime of a cohort. The postponement of fertility introduces distortions into this transposition. The completed fertility rate (CFR), on the other hand, presents the actual average number of children that women of a real cohort do have by the end of their childbearing years. The changes in completed fertility are often referred to as “quantum” effects, while the changes in timing of childbearing are often called “tempo” effects. The bottom line is that because of the postponement of births, TFRs underestimate somewhat the completed fertility that will be reached by the cohorts currently in childbearing ages.

A brief examination of how this works in practice - based on the Swedish case - can be found here.

The classic exposition of the tempo and quantum issues as put forward by John Bongaarts and Griffith Feeney can be found here in presentation form, and here in paper form.

A brief examination of how this works in practice - based on the Swedish case - can be found here.

The classic exposition of the tempo and quantum issues as put forward by John Bongaarts and Griffith Feeney can be found here in presentation form, and here in paper form.

Total fertillity rate (TFR) in Europe around 2003

Birth rates throughout Europe have declined to very low levels – currently the majority of countries have total fertility rates (TFR) which are registering below 1.5 children per woman. Several recent studies have suggested that this level might be a threshold that triggers self-reinforcing mechanisms, which tend to further suppress fertility. Hence, once TFR falls below 1.5, bringing it back up will be more dif- ficult. The Austrian Demographer Wolfgang Lutz has termed this situation a "low fertility trap". Most countries in Southern, Central and Eastern Europe - including the European parts of the former Soviet Union - seem to have fallen in this "trap". In addition, in a number of these countries the registered TFR is even below 1.3, a level that Kohler, Billari and Ortega refer to as "lowest low fertility". For a cross-section picture as of 2003 see the chart below.

(Please click over image for better viewing)

Very low fertility levels are no longer simply a European phenomenon. Several Asian countries have also fallen into the “low fertility trap” zone – Hong Kong was the first to do so in 1985, and has now been joined by Macao (with a TFR of below 1), Japan, the Republic of Korea and Singapore. In North America, Canada has been hovering just above the “trap” zone for a number of years now. In Latin America, Cuba registered a TFR of below 1.5 during the mid 1990s, but is now considered to be one of the few examples of a country where the Tfr seems to have returned above the 1.5 threshold (although, of course, whether there is much that is generalizable from this specific case seems to be rather doubtful).

(Please click over image for better viewing)

Very low fertility levels are no longer simply a European phenomenon. Several Asian countries have also fallen into the “low fertility trap” zone – Hong Kong was the first to do so in 1985, and has now been joined by Macao (with a TFR of below 1), Japan, the Republic of Korea and Singapore. In North America, Canada has been hovering just above the “trap” zone for a number of years now. In Latin America, Cuba registered a TFR of below 1.5 during the mid 1990s, but is now considered to be one of the few examples of a country where the Tfr seems to have returned above the 1.5 threshold (although, of course, whether there is much that is generalizable from this specific case seems to be rather doubtful).

TFRs in East and West Germany 1980 - 1999

Like other Eastern European countries, East Germany experienced a sharp and rapid decline in period fertility rates after the fall of communism. While there were still 180,000 births in 1990, there were only 110,000 a year later - a drop in the number of births by about 40 percent over the period of a single year. During this time, migration from East to West Germany had reduced the population size in the East considerably. In the period 1989 to 1991 alone, about one million East Germans had migrated to the West. In this sense the massive East to West migration has clearly distorted the usefulness of the annual number of births as a fertility indicator since the potential number of mothers has been considerably reduced.

However the total fertility rate (TFR), which standardizes for population size and age structure, does shows a drastic reduction in fertility. As can be seen from the graph below, the East German TFR dropped from 1.5 in 1990 to 1.0 in 1991, reaching its lowest level of 0.8 in the years 1992 to 1995. Since that time the East German TFR has steadily increased, but has still not reached West German fertility levels.

(Please click over image for better viewing)

Although, there is a general consensus that in the years immediately subsequent to unification East Germany underwent a fertility crisis, there has been some dispute about the general course of East German fertility. In particular it is possible to contrast two rival hypotheses: a crisis and an adaptation one. Advocates of the ‘crisis hypothesis’ argue that unfavorable economic constraints have kept East Germany’s fertility below West German levels and will continue to do so for the foreseeable future. Supporters of the ‘adaptation hypothesis’ are more optimistic in that they argue that even though the East Germany economic environment has significantly fallen behind the West German one, individuals in the neue Länder (new federal states) are now subject to very similar institutional constraints as their counterparts in the alte Länder (old federal states). Assuming that family policies, tax regulations and ultimately the entire welfare system are important parameters in fertility decisions, one might expect East German fertility to converge towards West German levels were the economic environment, and in particular the labour market conditions, to imporove. Advocates of the ‘crisis hypothesis’ have taken the drop in annual birth rates as an unmistakable sign of an East German fertility crisis, and have even honed down the crisis view to ask whether East Germany (and possibly even the whole of Germany) might not now be caught in a fertility trap.

Other have suggested that while this interpretation might have been correct for the years around unification, it has now become increasingly inapplicable. It is well known that period fertility indicators are questionable in their reliability as indicators of longer term fertility trends, and in particular when there are rapid changes in childbirth timing. A decline in period fertility rates can indicate a decline in lifetime fertility, but it might also be a reflection of the postponement of motherhood to higher ages. This aspect seems to be of particular importance in the case of East Germany. Like most other former Eastern Bloc countries the mean age of women at childbirth was very low in East Germany - when compared with Western Europe - at the end of the 1980s.

In 1989, the mean age at childbirth was just 24.7. On the other hand,the mean age at childbirth in West Germany was 28.3 in the same year.

This considerable difference in the age at childbirth between East and West Germans is crucial for understanding the depth of the ‘East German fertility decline’. Even if East German women, who were childless in 1990, temporarily gave up on childbearing during the upheavals of unification, they were generally young enough to postpone childbearing to later periods in their lives without hitting the biological limits to fertility. In other words, what looks like a fertility crisis from the point of period fertility indicators could in fact be a postponement of childbirth to West German age levels.

This being said, the ongoing level of fertility in West Germany is itself well below replacement, so that even a modest recovery in East German tfrs would hardly be a resolution of the German "fertility issue".

However the total fertility rate (TFR), which standardizes for population size and age structure, does shows a drastic reduction in fertility. As can be seen from the graph below, the East German TFR dropped from 1.5 in 1990 to 1.0 in 1991, reaching its lowest level of 0.8 in the years 1992 to 1995. Since that time the East German TFR has steadily increased, but has still not reached West German fertility levels.

(Please click over image for better viewing)

Although, there is a general consensus that in the years immediately subsequent to unification East Germany underwent a fertility crisis, there has been some dispute about the general course of East German fertility. In particular it is possible to contrast two rival hypotheses: a crisis and an adaptation one. Advocates of the ‘crisis hypothesis’ argue that unfavorable economic constraints have kept East Germany’s fertility below West German levels and will continue to do so for the foreseeable future. Supporters of the ‘adaptation hypothesis’ are more optimistic in that they argue that even though the East Germany economic environment has significantly fallen behind the West German one, individuals in the neue Länder (new federal states) are now subject to very similar institutional constraints as their counterparts in the alte Länder (old federal states). Assuming that family policies, tax regulations and ultimately the entire welfare system are important parameters in fertility decisions, one might expect East German fertility to converge towards West German levels were the economic environment, and in particular the labour market conditions, to imporove. Advocates of the ‘crisis hypothesis’ have taken the drop in annual birth rates as an unmistakable sign of an East German fertility crisis, and have even honed down the crisis view to ask whether East Germany (and possibly even the whole of Germany) might not now be caught in a fertility trap.

Other have suggested that while this interpretation might have been correct for the years around unification, it has now become increasingly inapplicable. It is well known that period fertility indicators are questionable in their reliability as indicators of longer term fertility trends, and in particular when there are rapid changes in childbirth timing. A decline in period fertility rates can indicate a decline in lifetime fertility, but it might also be a reflection of the postponement of motherhood to higher ages. This aspect seems to be of particular importance in the case of East Germany. Like most other former Eastern Bloc countries the mean age of women at childbirth was very low in East Germany - when compared with Western Europe - at the end of the 1980s.

In 1989, the mean age at childbirth was just 24.7. On the other hand,the mean age at childbirth in West Germany was 28.3 in the same year.

This considerable difference in the age at childbirth between East and West Germans is crucial for understanding the depth of the ‘East German fertility decline’. Even if East German women, who were childless in 1990, temporarily gave up on childbearing during the upheavals of unification, they were generally young enough to postpone childbearing to later periods in their lives without hitting the biological limits to fertility. In other words, what looks like a fertility crisis from the point of period fertility indicators could in fact be a postponement of childbirth to West German age levels.

This being said, the ongoing level of fertility in West Germany is itself well below replacement, so that even a modest recovery in East German tfrs would hardly be a resolution of the German "fertility issue".

Percentage of out-of-wedlock births in France, Germany, Italy, Spain, Sweden, and the United Kingdom, 1960–1995

A close look at the data suggests reveals no clearcut correlation between family formation/dissolution patterns and fertility levels. The percentage of “illegitimate” births in Mediterranean Europe was minimal before the 1980s and in Italy and Spain even only reached a rate of about 1 out of 10 births by the mid 1990s.

In contrast this proportion reaches approximately one-third of all births in France and the United Kingdom and over one-half of those in Sweden by the 1990s. This percentage tends to rise steadily from year to year in spite of sizable short-term fertility fluctuations, especially in Sweden and France. In the case of Germany, however, it is noticeable that the percentage of children born out of wedlock had stabilized by the 1990s (around one-sixth): this is an interesting result since marriage and the family are protected by the German Constitution and since unification the number of births has been halved in the east, where “illegitimacy” was previously massive (See table below). Countries with so-called traditional family structures (high marriage rate, low divorce rate, low illegitimacy rate, etc.) like Italy and Spain were totally “detraditionalized” in terms of fertility in less than two decades. The level of births in these two countries has plummeted to previously wholly unpredicted levels. No official population forecast, either national or international, had anticipated a total fertility rate of 1.2 for any country, and least of all for the Mediterranean countries, which are still commonly viewed as “laggards” and often as being family-oriented. This outcome is probably the biggest surprise in European demographics as it entered the present century.

(Please click over image for better viewing)

In contrast this proportion reaches approximately one-third of all births in France and the United Kingdom and over one-half of those in Sweden by the 1990s. This percentage tends to rise steadily from year to year in spite of sizable short-term fertility fluctuations, especially in Sweden and France. In the case of Germany, however, it is noticeable that the percentage of children born out of wedlock had stabilized by the 1990s (around one-sixth): this is an interesting result since marriage and the family are protected by the German Constitution and since unification the number of births has been halved in the east, where “illegitimacy” was previously massive (See table below). Countries with so-called traditional family structures (high marriage rate, low divorce rate, low illegitimacy rate, etc.) like Italy and Spain were totally “detraditionalized” in terms of fertility in less than two decades. The level of births in these two countries has plummeted to previously wholly unpredicted levels. No official population forecast, either national or international, had anticipated a total fertility rate of 1.2 for any country, and least of all for the Mediterranean countries, which are still commonly viewed as “laggards” and often as being family-oriented. This outcome is probably the biggest surprise in European demographics as it entered the present century.

(Please click over image for better viewing)

Number of women with 3 or more children for the birth cohorts 1935 to 1960 in 6 EU Countries

One factor influencing the birth rate level of a country is the number of women who have children, and in particular the proportion of women having children in what are called the "higher order parities" - ie more than three children. The number of German women giving birth to three or more children is lower than in other European countries. Using data from Eurostat, it can be seen from the graph below that the percentage of families with three and more children already stopped declining with the cohort of women born in 1945. Around one of five German women born between 1945 and 1960 decided to have three children or more, while in France every third woman did.

(Please click over image for better viewing)

It is often assumed that the high rate of childlessness in Germany is the principal reason for Germany's continuiong low birth rate of below 1.5 children per woman. However, breaking down birth rate in terms of first, second, third and fourth children shows that replacement level fertility in France is sustained both by the higher proportion of women who have a child, by very second child fertility rates and by comparatively high fertility rates for birth orders of three and above (see chart below). In Finland and Great Britain there are proportionally as many third and higher order births as in France, but there are fewer first and second order births. As a result, the total fertility rate is 0.2 children per women below replacement. In Germany, birth rates of all orders are low, but while the difference between Germany and France is just 18 children per 100 women due to a higher rate of childlessness, the differences due to lower second, third and forth order births amount to 35 children per 100 women taken collectively. In short, the gap between France and Germany is severely aggravated by the fact that fewer women decide to have two or more children, and is not simply the result of a higher rate of German childlessness.

(Please click over image for better viewing)

(Please click over image for better viewing)

It is often assumed that the high rate of childlessness in Germany is the principal reason for Germany's continuiong low birth rate of below 1.5 children per woman. However, breaking down birth rate in terms of first, second, third and fourth children shows that replacement level fertility in France is sustained both by the higher proportion of women who have a child, by very second child fertility rates and by comparatively high fertility rates for birth orders of three and above (see chart below). In Finland and Great Britain there are proportionally as many third and higher order births as in France, but there are fewer first and second order births. As a result, the total fertility rate is 0.2 children per women below replacement. In Germany, birth rates of all orders are low, but while the difference between Germany and France is just 18 children per 100 women due to a higher rate of childlessness, the differences due to lower second, third and forth order births amount to 35 children per 100 women taken collectively. In short, the gap between France and Germany is severely aggravated by the fact that fewer women decide to have two or more children, and is not simply the result of a higher rate of German childlessness.

(Please click over image for better viewing)

Mean Age of Women At First Childbirth, Europe 2003

The map in below presents the mean ages of mothers at first birth in Europe around 2003, and shows the extent of postponement in the timing of parenthood. To put these data in perspective -- in 1975 the highest mean age at first birth registered in Europe was 25.7 (in Switzerland), and in the majority of countries the indicator was between 22 and 24 years. Most researchers interpret this as part of the general trend towards postponement of choices that are irreversible or hardly reversible, usually associated with the ideational and other changes linked to the so-called “second demographic transition”. Again in line with the predictions of the second demographic transition theory about the importance of individual autonomy and self-expression, the differences between individuals within a population in the timing of parenthood are also increasing.

(Please click over image for better viewing)

(Please click over image for better viewing)

Low Fertility Hypothesis

In a recent post on Demography Matters Claus offered a nice summary of the latest revision of the low fertility trap hypothesis as advanced by Wolfgang Lutz et al. As summarized below, there are three basic components to this hypothesis:

As Lutz says the key idea is that once fertility falls below a certain level (and even in the event that the hypothesis proved to be well founded this level could only be determined empirically, on the basis of actual experience) a self-reinforcing demographic regime may be established from which it is hard to escape, in the sense of raising fertility back up towards replacement levels. The cut-off point which Lutz et al start from is 1.5 (and in this they take their lead from a proposal by Peter Macdonald in this paper ). This figure does seem to have some coherence in terms of actual experience to date, since with the exception of Denmark - which did briefly fall under 1.5 tfr in the 1990s - no country seems to have gone below it and come back up again.

continue reading

As Lutz says the key idea is that once fertility falls below a certain level (and even in the event that the hypothesis proved to be well founded this level could only be determined empirically, on the basis of actual experience) a self-reinforcing demographic regime may be established from which it is hard to escape, in the sense of raising fertility back up towards replacement levels. The cut-off point which Lutz et al start from is 1.5 (and in this they take their lead from a proposal by Peter Macdonald in this paper ). This figure does seem to have some coherence in terms of actual experience to date, since with the exception of Denmark - which did briefly fall under 1.5 tfr in the 1990s - no country seems to have gone below it and come back up again.

continue reading

Saturday, June 16, 2007

Net reproduction rate in France, Germany, Italy, and the United Kingdom, 1900–1995

Another characteristic of the Swedish pattern is that Sweden, along with France and the United Kingdom, was one of the few EU countries where the total fertility rate never fell below the level of 1.6 children per woman. A historian of the welfare state might be tempted to remind us that public officials in these three countries feared a population decline in the 1930s and that the creators of the social security systems (William Henry Beveridge in England, Pierre Laroque in France, and the Nobel Prize winner Alva Myrdal in Sweden) had comparable views — i. e., pronatalist —on population matters and implemented a family-oriented social policy at the time of World War II. This explicit demographic preoccupation progressively eroded or vanished in the following decades, but family support is still a non-negligible component of the welfare state. Few experts could imagine that the Italian TFR was going to go lower than the British rate in the 1950s and 1960s (See Table Below).

(Please click over image for better viewing)

(Please click over image for better viewing)

Total fertility rate in France, Germany, Italy, Spain, Sweden, and the United Kingdom, 1960–1996

To design a population policy, the decision maker has to use an index that is not biased by age structure and that reflects the sheer propensity to have children: the total fertility rate. The indicator is permanently calculated for the purpose of international comparisons, and it is widely produced to show the impact of a given plan (antinatalist or pronatalist) of action. The table below shows that the European trends are radical. In most of the “big” countries of the EU, the total fertility rate fell on average by 1.0 to 1.4 children per woman. In Spain, the decline was much sharper: 2.90 at the beginning of the 1960s but only 1.15 in 1996, 1.75 in absolute terms and hence a relative decline of 60%. There is no more Mediterranean or Catholic fertility, since Italy and Spain have experienced the lowest fertility ever seen in the history of mankind.

(Please click over image for better viewing)

A comparison between northern and southern Europe through the examples of Sweden and Italy is instructive. Until the 1970s the Swedish fertility rate was lower than the Italian rate, and it was under the EU curve (See Graph Below). Now the opposite is true; new generations of Swedish women have more children than corresponding Italian women.

(Please click over image for better viewing)

A comparison between northern and southern Europe through the examples of Sweden and Italy is instructive. Until the 1970s the Swedish fertility rate was lower than the Italian rate, and it was under the EU curve (See Graph Below). Now the opposite is true; new generations of Swedish women have more children than corresponding Italian women.

Number of births in France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and the United Kingdom, 1960–1995

In the United Kingdom as well as in Italy, the annual number of births in the mid- 1960s was close to 1 million; it has fallen by one-quarter in the United Kingdom and by nearly one-half in Italy. In Germany, the absolute decline is still more impressive: 1.3 million in 1965 compared to about 0.8 million in 1995; the difference is 500,000 births per year (See table below). The case of France differs for two reasons: there the fertility decrease was not as steep as in neighboring countries of continental Europe, and the age structure had a protective impact; France had more baby boomers at childbearing ages. These crude data on births are important because they shape the age structure, and finally they constitute the most essential variable for political authorities at all levels (local, regional, national, and international). Under present conditions of very low mortality, they determine the number of students, the number of future inflows in the labor market, the number of consumers, of taxpayers, etc.; they have a decisive impact on long-range variations in demand, on investment (infrastructure, housing), and on corresponding sectorial labor needs (teachers, doctors, builders, etc.).

(Please click over image for better viewing)

(Please click over image for better viewing)

Population of the five largest member countries of EU-15 .

The movement towards population stagnation has been similar for all nations within the European Union. To simplify the presentation, we have produced population figures for the five largest member countries at the turn of the century (France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and the United Kingdom), which together comprise 80% of the total population of EU- 15. The German population has tended to stabilize around 80 million; the French, Italian, and British a bit below 60 million; and the Spanish slightly below 40 million (See table below). Leaving aside immigration, the total population of these five countries could peak at about 300 million and then, if present fertility trends persist, begin to shrink.

(Please click over image for better viewing)

(Please click over image for better viewing)

Population, natural increase, and net migration in the EU-15, 1960–1995

In the old EU-15, the rate of population growth has been slowing down and is now close to zero; immigration is the unique factor that has had a dampening effect on this slackening process (in many cases, it prevents straightforward depopulation.

Between the mid-1960s and the mid-1990s, the natural increase fell by more than two million, from 2.56 million in 1965 to 0.33 million in 1995. As the number of deaths was approximatively constant, this phenomenon essentially can be attributed to a substantial drop in the number of births, which declined by more than one-third in only three decades (from 6.1 million in 1965 to 4.0 million in 1995). Despite the fact that in 2000 the EU has 100 million more inhabitants than the United States (370 million versus 270 million), the number of births in the mid 1990s was similar (3.915 million in the United States in 1996). During the last few years, for the first time in the history of the European community, the contribution of immigration to population growth has becopme stronger (indeed, much stronger) than the impact of natural increase (which, in turn, is stimulated by past immigration), as the table below indicates. The lesson is clear: the EU is entering a new historical stage, the age of migratory dependency.

(Please click over image for better viewing)

Between the mid-1960s and the mid-1990s, the natural increase fell by more than two million, from 2.56 million in 1965 to 0.33 million in 1995. As the number of deaths was approximatively constant, this phenomenon essentially can be attributed to a substantial drop in the number of births, which declined by more than one-third in only three decades (from 6.1 million in 1965 to 4.0 million in 1995). Despite the fact that in 2000 the EU has 100 million more inhabitants than the United States (370 million versus 270 million), the number of births in the mid 1990s was similar (3.915 million in the United States in 1996). During the last few years, for the first time in the history of the European community, the contribution of immigration to population growth has becopme stronger (indeed, much stronger) than the impact of natural increase (which, in turn, is stimulated by past immigration), as the table below indicates. The lesson is clear: the EU is entering a new historical stage, the age of migratory dependency.

(Please click over image for better viewing)

Births in Europe In the Twentieth Century

On the eve of World War I, the average number of annual births in Europe was 10 million for a total population of 300 million inhabitants; by the year 1995, this number had dropped to 6 million for a corresponding population of 500 million; hence, the population had increased by two-thirds while the number of births fell by 40%. Such a decline was structural and even rather linear; the following data represent the number of births (in thousands) from decade to decade throughout the twentieth century:

The post-World War II baby boom was limited in time, space, and magnitude; it occurred only among the Western allies and its duration was usually short (15 to 20 years). In 1960 as well as in 1950, the number of births in Europe was similar to its 1940 level: around 8 million; the idea of a fertility cycle had no meaning for Europe as a whole. The 1940s and 1950s marked a stagnation, not an upswing. Then the secular movement resumed steadily, but it is very difficult to predict the bottom line since we have no comparable reference in our past. In 1996 the total fertility rate for Europe, with or without the European part of the former Soviet Union, was 1.4 — the lowest in the world. For Europe alone the birth deficit — defined by the difference between the number of births required for replacement and the number observed — is now in the region of about 2 million per year.

The post-World War II baby boom was limited in time, space, and magnitude; it occurred only among the Western allies and its duration was usually short (15 to 20 years). In 1960 as well as in 1950, the number of births in Europe was similar to its 1940 level: around 8 million; the idea of a fertility cycle had no meaning for Europe as a whole. The 1940s and 1950s marked a stagnation, not an upswing. Then the secular movement resumed steadily, but it is very difficult to predict the bottom line since we have no comparable reference in our past. In 1996 the total fertility rate for Europe, with or without the European part of the former Soviet Union, was 1.4 — the lowest in the world. For Europe alone the birth deficit — defined by the difference between the number of births required for replacement and the number observed — is now in the region of about 2 million per year.

Total Fertility Rate England and France 1750 to 2000

Fertility in the UK and France 1750 to 2000

British and France were the first really modern nation-states and, as a consequence, were among the first (along with Sweden and the Netherlands) to enter the demographic transition. The French Revolution marked the beginning of the secular fertility decline in France, whereas the industrial revolution in England encouraged family formation (earlier marriage, higher fertility). Throughout the nineteenth century, the fertility gap between these two nations was hugely detrimental to France as can be seen from the graph.

(Please click over image for better viewing)

During the 1800–1880 period, the difference between Britain and France ranged between 1.3 and 1.8 children per woman: that is the same value as the difference between the prevailing present fertility and zero. This fertility differential evidently had tremendous implications for foreign policy and for the fate of the future European colonies. As a consequence of this relative differential France lost its position of leadership to England; the French language regressed all over Europe and, contrary to English, never acquired a world status; moreover, French emigration was very limited. By contrast, from the beginning of the nineteenth century British emigrants exported their ideas, their ideals, and their language on all continents. In “northern” America (north of the Rio Grande), only 2% of the entire population (namely,the population which is to be found in Quebec) uses the French language to communicate in daily life.

As can also be seen above, staring at the turn of the 19th century French fertility has gradually regained its relative position vis-a-vis the UK.

(Please click over image for better viewing)

During the 1800–1880 period, the difference between Britain and France ranged between 1.3 and 1.8 children per woman: that is the same value as the difference between the prevailing present fertility and zero. This fertility differential evidently had tremendous implications for foreign policy and for the fate of the future European colonies. As a consequence of this relative differential France lost its position of leadership to England; the French language regressed all over Europe and, contrary to English, never acquired a world status; moreover, French emigration was very limited. By contrast, from the beginning of the nineteenth century British emigrants exported their ideas, their ideals, and their language on all continents. In “northern” America (north of the Rio Grande), only 2% of the entire population (namely,the population which is to be found in Quebec) uses the French language to communicate in daily life.

As can also be seen above, staring at the turn of the 19th century French fertility has gradually regained its relative position vis-a-vis the UK.

Regional Divergence in Germany

Since reunification, approximately 1.5 million people have left the former East Germany. In the states of Thuringia, Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt and Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, population numbers have reduced by between eight and twelve percent, since the time of reunification. In the western states there are also shrinking regions: in the Ruhr Basin, Saarland and along the former German-German border. Economically strong areas in the West have profited from the migration of young and qualified people. Particularly Bavaria and Baden-Wurttemberg have been able to increase their population, and both states continue to benefit from internal migration.

(Please click over image for better viewing)

Source: Berlin Institute For Population Development

(Please click over image for better viewing)

Source: Berlin Institute For Population Development

Childless Women in Six EU Countries

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)